Eggs and the Environment

Photo credits: Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals

The uncomfortable truth: there is no environmentally sustainable way to produce eggs when plant-based alternatives exist that provide equivalent nutrition at a fraction of the ecological cost.

The Environmental Footprint of Eggs

Understanding Egg Production's Environmental Impact

Comparing Eggs to Plant-Based Proteins: The Scale of Difference

Feed: The Dominant Environmental Driver

Production Systems: No Sustainable Choice

Contents:

Greenwashing and Industry Narratives

The Bottom Line: When Alternatives Exist, Eggs Aren't Sustainable

Take Action

The Environmental Footprint of Eggs

Key Facts at a Glance

Egg production generates 5 to 10 times more greenhouse gas emissions than plant-based proteins like tofu, lentils, and peas — even in the most "efficient" systems.[1][2][3]

The egg industry's celebrated environmental improvements since 1960 came primarily from one source: forcing hens to produce 67-178% more eggs through genetic manipulation, intensifying the exploitation of individual birds. [4][5]

Feed production accounts for 50-75% of egg production's total environmental footprint, driven by resource-intensive cereals and soy that require synthetic fertilizers, land clearing, and long-distance transport. [6][7][8]

"Higher welfare" systems like organic and free-range often have worse environmental impacts than cage systems — organic eggs can require up to 2.7 times more feed and generate 40-65% higher emissions. [7][9]

Switching from any egg system to plant-based proteins reduces land use by 60-75%, water use by 50-70%, and emissions by 80-90% for equivalent protein. [1][2][3]

Image caption

Understanding Egg Production's Environmental Impact

Global egg production supplies over 80 million metric tons of eggs annually, making it a significant component of the global food system.[6][10] The industry promotes eggs as an efficient animal protein with lower environmental impacts than beef, pork, or chicken meat. While this comparison is technically accurate, it obscures a more important reality: eggs still generate dramatically higher environmental impacts than plant-based proteins across every metric. [1][2][3][11]

When industry reports celebrate reduced environmental footprints, they measure efficiency per kilogram of eggs produced. What they don't emphasize is how those efficiency gains were achieved: primarily by breeding hens to produce far more eggs than their bodies were designed to handle, causing widespread physical deterioration and suffering that enables the appearance of environmental progress. [4][5][12]

(*For more on the animal welfare costs of egg production, see our dedicated welfare page.*)

The Numbers Behind the Industry Narrative

Between 1960 and 2010, the US egg industry reported substantial environmental improvements per kilogram of eggs produced: [4][5]

71% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions

71% reduction in eutrophying emissions

65% reduction in acidifying emissions

31% reduction in energy use

81% reduction in land use

These figures appear in industry sustainability reports and are frequently cited as evidence of agricultural innovation and environmental responsibility. However, analysis of the underlying data reveals that 28-43% of these improvements came from what industry calls "bird performance"— a euphemism for genetic manipulation that forces modern hens to lay 300-500 eggs per year compared to 180-250 eggs in 1960. [4][5] This represents a 67-178% increase in productivity per hen, achieved through selective breeding that optimizes hens' bodies for maximum egg output regardless of the physical toll. [4][5][12]

An additional 30-44% of improvements came from feed composition changes, primarily shifting from animal-derived ingredients to plant-based sources, and 27-30% from background industrial efficiencies in fertilizer production and transport. [4][5] While these latter factors represent genuine improvements in agricultural systems, the largest single contributor to reduced environmental impact per egg remains the intensification of individual hen exploitation.

Importantly, despite these per-unit improvements, total US egg production increased 30% from 1960 to 2010 (from 59.8 to 77.8 billion eggs). [4][5] This means that while efficiency improved, the absolute environmental footprint of the industry remained substantial and continues to grow with global demand.

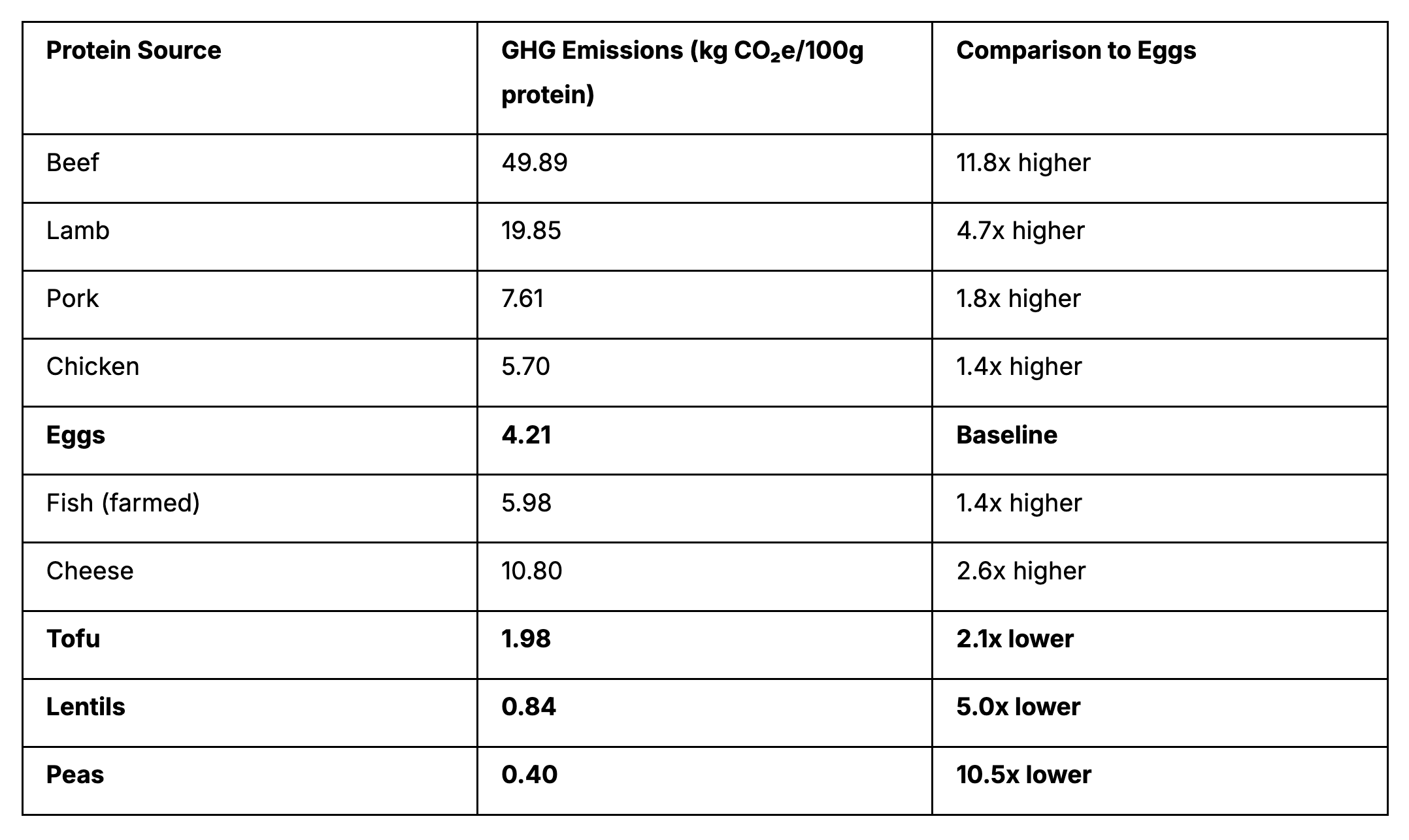

Comparison of greenhouse gas emissions across protein sources shows eggs have a lower carbon footprint than most animal proteins but higher than plant-based alternatives.

Comparing Eggs to Plant-Based Proteins: The Scale of Difference

The most critical environmental comparison isn't between eggs and beef—it's between eggs and the plant-based proteins that can replace them nutritionally. When evaluated per unit of protein, the differences are stark and unambiguous.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Eggs produce approximately 4.21 kg CO₂-equivalent per 100 grams of protein —significantly lower than beef (49.89 kg), lamb (19.85 kg), pork (7.61 kg), and even chicken meat (5.70 kg). [1][2][11] Industry materials frequently highlight this comparison to position eggs as an environmentally responsible protein choice.

However, when compared to plant-based proteins, the picture changes dramatically: [1][2][3][11]

Tofu: 1.98 kg CO₂e per 100g protein (53% lower than eggs)

Lentils: 0.84 kg CO₂e per 100g protein (80% lower than eggs)

Peas: 0.40 kg CO₂e per 100g protein (90% lower than eggs)

This means that switching from eggs to lentils reduces climate impact by a factor of five. Switching to peas reduces it by a factor of ten. Even in the most efficient egg production systems, emissions remain 5-10 times higher than plant proteins providing equivalent nutrition. [1][2][3]

When measured per kilogram of protein rather than per 100 grams, one study found that free-range eggs produce only 0.2 kg CO₂e — lower than all meat sources. [13][14] While this figure appears favorable, it still represents substantially higher impact than tofu and exponentially higher impact than legumes, which produce negligible emissions per kilogram of protein.

Water and Land Use

Resource efficiency follows similar patterns. Eggs require approximately 53-60 liters of water per kilogram of eggs, which translates to significantly less water than beef and about 75% less than chicken meat on a per-calorie basis. [6][10][15] However, when compared to plant proteins, eggs still require similar or higher water inputs — approximately 1.07 times the water required by beans when normalized for protein content. [11]

Land use presents an even more striking contrast. Eggs require approximately 5.9 m² per kilogram of protein, compared to 164 m² for beef. [11] Industry frequently cites this 28-fold difference as evidence of sustainability. Yet beans require less than half the land of eggs —eggs demand 2.43 times more land than kidney beans for equivalent protein. [11] In absolute terms, shifting from eggs to plant proteins could reduce land use by 60-75% while providing the same nutritional value. [2][3][11]

Energy Consumption

Energy use in egg production ranges from 12.3 to 20 MJ per kilogram of eggs, depending on the production system, with feed production accounting for 50-75% of total energy consumption. [6][7][8] Plant-based proteins typically require 3-5 MJ per kilogram of protein equivalent — representing a 60-75% reduction in energy demand. [2][3]

The table below summarizes these critical comparisons:

Source: Compiled from multiple life cycle assessments and meta-analyses [1][2][3][11]

Image caption

Across all credible life cycle assessments of egg production, feed emerges as the single largest contributor to environmental impacts, accounting for 50-75% of the total footprint depending on the impact category examined. [6][7][8] In Czech Republic production systems, feed represented approximately 50% of total environmental impact across all housing systems studied. [7][9] US research found that feed accounts for 54-75% of primary energy use and 64-72% of global warming potential in egg production. [7][8]

Feed: The Dominant Environmental Driver

Why Feed Dominates the Footprint

The environmental burden of feed stems from multiple sources throughout the production chain: [6][7][8]

Synthetic nitrogen fertilizer production represents one of the largest contributors to feed-related emissions. Manufacturing nitrogen fertilizer requires substantial energy inputs and generates significant greenhouse gas emissions. These fertilizers are applied to cereal crops (corn, wheat, barley) and soy that form the foundation of laying hen diets. [6][7]

Land use change associated with expanding soy and cereal production drives deforestation and habitat destruction, particularly in South America where much of the world's soy is grown. Currently, over 80% of the world's soybean crop goes to feeding livestock, including egg-laying hens. [6][10] This represents a direct competition between animal agriculture and more efficient food production systems.

Long-distance transport of feed ingredients adds substantially to the carbon footprint. Soy from Brazil or Argentina, corn from the American Midwest, and other ingredients travel thousands of kilometers before reaching egg production facilities. [6][7] One UK study found that approximately 63% of egg production emissions represent embodied carbon in poultry feed, primarily from these cereals and soy with associated high emissions from industrial nitrogen production, land-use change, and transport. [13][14]

Image caption

Feed Conversion Ratio: The Critical Metric

The feed conversion ratio (FCR) — the amount of feed required to produce one kilogram of eggs—stands as the most critical factor influencing environmental performance. [6][7][8][9] Small changes in FCR create cascading effects across all environmental impact categories because they directly determine the quantity of resource-intensive feed required.

US egg production FCR improved dramatically from 3.44 in 1960 to 1.98 in 2010, representing a 42% improvement that contributed substantially to the reduced environmental impacts celebrated by industry. [4][5] However, this improvement was achieved primarily through genetic selection that bred hens whose bodies convert feed to eggs with maximum efficiency—regardless of the physical consequences for the birds themselves. [4][5][12]

Contemporary facilities report FCR ranging from 1.76 to 2.32, with continued genetic selection pressure to reduce this ratio further. [4][5] Different housing systems show varying feed efficiencies, which partially explains their differing environmental impacts: [7][9]

Battery and enriched cage systems: 1.98-2.2 FCR

Barn/cage-free systems: 2.2-2.4 FCR

Free-range systems: 2.0-2.6 FCR

Organic systems: 2.7-5.3 FCR

The dramatically higher FCR in organic systems—sometimes reaching 5.3—reflects lower hen productivity due to breed characteristics, feed quality variations, outdoor activity levels, and management practices. [7][9] This translates directly into proportionally higher environmental impacts across all categories.

Feed Composition and Sourcing

Changes in feed composition accounted for 30-44% of the environmental improvements observed in US egg production between 1960 and 2010. [4][5] The shift from animal-derived feed ingredients to plant-based sources, particularly the replacement of ruminant materials with porcine and poultry by-products and then increasingly to pure plant sources, reduced impacts substantially. [4][5]

However, heavy dependence on cereals and soy remains an environmental concern due to the associated emissions from nitrogen fertilizer production, land-use change, and long-distance transport discussed above. [6][7][13] The crude protein content of feed significantly influences environmental impacts through nitrogen excretion and subsequent ammonia emissions. Optimal protein formulation tailored to hen nutritional requirements at different life stages can reduce impacts without compromising production. [7][8]

Research on alternative feed sources—including insect proteins, agricultural by-products, food waste, and locally-sourced ingredients—shows promise for reducing the environmental footprint of egg production. [6][7][8] However, these alternatives face challenges related to nutritional adequacy, cost, availability at scale, and regulatory approval. More fundamentally, they don't address the core issue: even with optimized feed, egg production still requires substantially more resources than producing plant proteins directly.

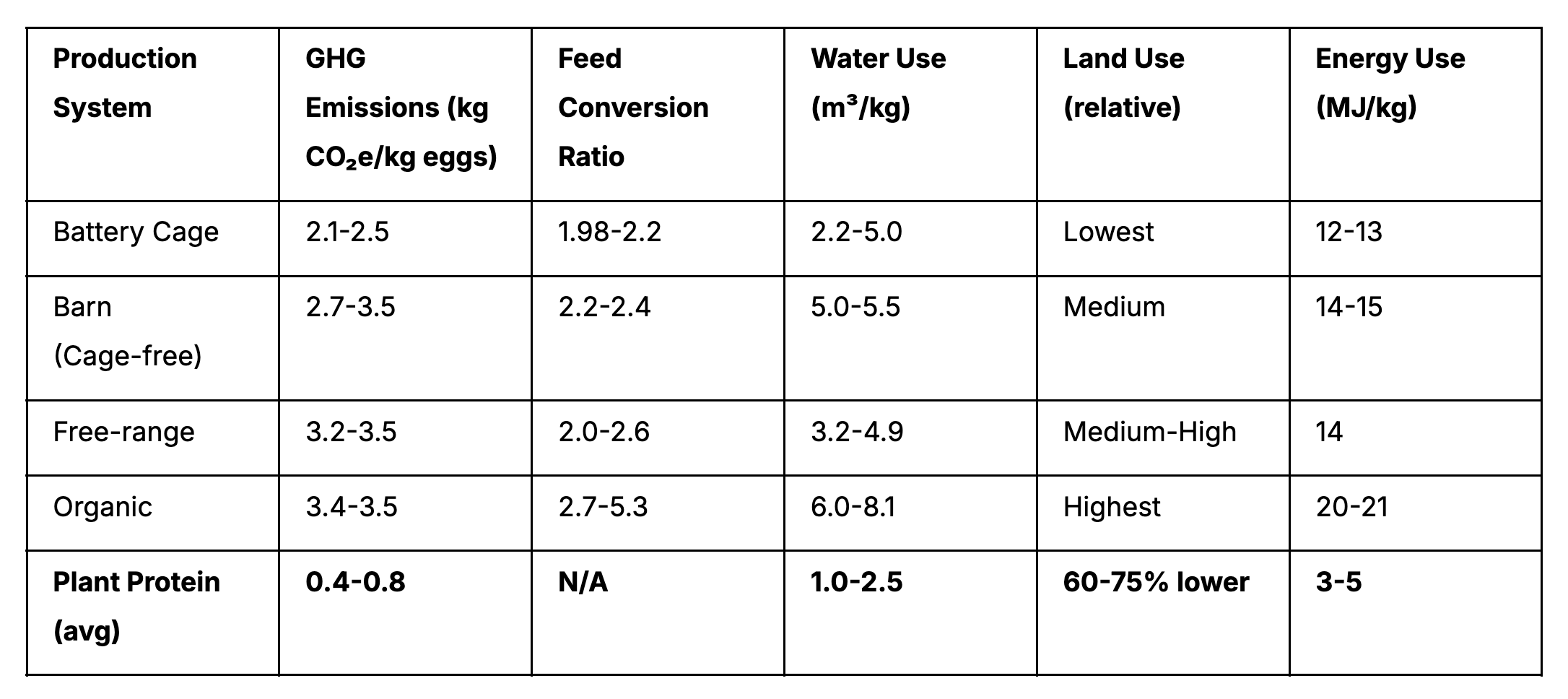

Production Systems: No Sustainable Choice

The egg industry offers consumers a spectrum of production systems—battery cages, enriched cages, barn/cage-free, free-range, organic, and pasture-raised. Marketing materials and retailer messaging frame these as meaningful environmental and ethical choices, with "higher welfare" and "sustainable" labels commanding significant price premiums. The reality revealed by comprehensive life cycle assessments: all systems involve substantial environmental impacts, and some "higher welfare" systems actually generate worse environmental outcomes than intensive confinement. [7][9][10]

The table below summarizes environmental performance across major production systems:

Based on equivalent protein from legumes/tofu [1][2][3][7][9]

Battery and Enriched Cages: Environmental Efficiency Through Extreme Confinement

Conventional battery cages and enriched/furnished cages remain common globally, though increasingly restricted or banned in Europe and parts of North America due to welfare concerns.<sup>6,10,12</sup> From a purely environmental perspective, cage systems demonstrate measurable advantages over alternative systems: they typically achieve the **lowest greenhouse gas emissions** (2.1-2.5 kg CO₂e per kg eggs), best feed conversion ratios (1.98-2.2), and most efficient resource use per unit of production.<sup>7,9,10</sup>

These efficiencies stem from environmental control that optimizes temperature, minimizes hen activity and associated energy expenditure, reduces mortality through isolation from disease vectors, and maximizes stocking density to reduce facility footprint per bird.<sup>6,7,9</sup> Manure management in cage systems is also more controlled, with belts or scrapers that facilitate collection and reduce ammonia emissions compared to floor systems where manure accumulates.<sup>6,7</sup>

However, even these “most efficient” systems still generate **5-10 times higher emissions** than plant-based proteins providing equivalent nutrition.<sup>1,2,3</sup> The environmental efficiency is achieved through extreme confinement—hens in battery cages have just 432-750 cm² of space (less than an A4 sheet of paper), cannot spread their wings, perch, nest, or dust bathe, and suffer from numerous welfare problems including bone fractures, foot injuries, and behavioral deprivation.<sup>6,10,12</sup> (*For detailed welfare information, see our dedicated animal welfare page.*)

The European Union banned conventional battery cages in 2012, though "enriched" or "furnished" cages with slightly more space and minimal amenities remain permitted.<sup>10,12</sup> Despite the environmental efficiencies, consumer rejection of caged eggs continues to drive industry transformation globally.

Should You Rescue Chickens Instead?

Some people encountering this information ask about rescuing chickens rather than buying them from hatcheries. This is a compassionate impulse, but it requires understanding the full picture.

Rescued chickens still carry the genetic damage. Whether from a commercial operation or a backyard farm, they remain in bodies that hurt. The osteoporosis, reproductive disorders, and chronic pain don't disappear with better care.[15][16] Managing that suffering requires substantial financial commitment (potentially 5-10 years of daily care and veterinary expenses) and emotional labor.[28][29]

Eggs must be managed appropriately. Many rescued hens continue laying despite poor health. Those eggs should be returned to the hens (crushed and mixed back into their food) to recycle lost calcium.[28] The situation becomes managing an ongoing health crisis, not benefiting from the bird's output.

Rescuing a chicken is an act of care for an individual being in distress. It's not a solution to systemic chicken suffering. It's a band-aid on a much larger problem.

Organizations like Animal Place, Farm Sanctuary, United Poultry Concerns, and Open Sanctuary Project provide resources for ethical rescue and care.[28][29][30][31][32]

The Fundamental Problem

Keeping backyard chickens (whether purchased from a hatchery or rescued from a farm) doesn't opt anyone out of animal exploitation. It replicates the same patterns on a smaller scale, often with more emotional proximity.

If the goal is to reduce participation in systems that harm animals, keeping chickens for eggs isn't the answer.

Image caption

What Actually Reduces Harm

Action: Stop consuming eggs

How It Helps:

The most direct action. Plant-based alternatives exist for baking, cooking, and eating. The egg industry's messaging suggests eggs are nutritionally irreplaceable; they're not. Alternatives exist and work well.

Action: Support farmed animal sanctuaries

How It Helps:

Organizations like Animal Place, Farm Sanctuary, United Poultry Concerns, and Open Sanctuary Project rescue and care for chickens and other farmed animals who have been abandoned or rescued from bad situations.[28][29][30][31][32]

They provide legitimate sanctuary (space to live out their lives without expectation of production). Supporting them through donation, volunteering, or education addresses the crisis without replicating exploitation. Find sanctuaries at sanctuaries.org or through United Poultry Concerns.[28][29]

Action: Advocate for policy change

How It Helps:

Support legislation that prohibits cruel practices like male chick culling, improves conditions for laying hens, funds research into alternatives to animal agriculture, and holds producers accountable for welfare standards.[7][33][34]

USDA initiatives like biosecurity improvements and avian flu prevention programs affect industry practices.[33][34] Personal choices matter, but systemic change requires collective action.

Action: Educate others

How It Helps:

Share what's been learned about backyard chicken keeping, the egg industry, and where chicks really come from. Help people make informed decisions rather than impulse decisions.

University extension resources from institutions like Colorado State, Virginia Tech, University of Florida, University of Maryland, and University of Wisconsin provide evidence-based information.[19][20][21][35][12][11][14]

Final Thoughts

The backyard chicken boom is driven by good intentions. People want agency over their food sources. They want to make ethical choices. They want to escape participation in systems they recognize as harmful.

These motivations are understandable. But understanding and action sometimes diverge.

Keeping backyard chickens (for eggs, pest control, companionship, or any other reason) doesn't represent escape from exploitation. It represents participation in it, on a smaller and more personal scale.

Chickens deserve better.

They deserve not to be bred into bodies that hurt them.

They deserve not to be valued primarily for what they produce.

They deserve not to exist for human purposes.

Please, leave eggs off your plate.

-

San Antonio News - "America's backyard chicken boom explained" (October 2025) https://san.com/cc/americas-backyard-chicken-boom-explained/

Ainvest - "Americans raising backyard chickens surge by 28%" (April 2025) https://ainvest.com/news/chicken-boom

Audacy - "Backyard chicken ownership is skyrocketing" (February 2025) https://audacy.com/articles/news/backyard-chicken-ownership-is-skyrocketing

National Center for Biotechnology Information - "From the Backyard to Our Beds: The Spectrum of Care" (January 2024) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10814380/

Mike the Chicken Vet - "Major US Study on Backyard Flocks" (June 2013) https://mikethechickenvet.wordpress.com/

Forbes - "How The 2024 Bird Flu Outbreak Is Impacting Our Food" (May 2024) https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2024/05/01/how-the-2024-bird-flu-outbreak-is-impacting-our-food/

ASPCA - "Hatching a Plan to End a Cruel Practice" (March 2025) https://www.aspca.org/news/hatching-plan-end-cruel-practice

Kipster - "Egg Producer Kipster Uses In Ovo Sexing Technology" (June 2025)

Meyer Hatchery Blog - "How Long Do Chickens Live? Factors That Impact Lifespan" (December 2024) https://blog.meyerhatchery.com/how-long-do-chickens-live

Purina Mills - "How Egg Production is Affected by Age" (January 2025) https://www.purinamills.com/chicken-feed/articles/how-egg-production-is-affected-by-age

University of Florida IFAS Extension - "Factors Affecting Egg Production in Backyard Chicken Flocks" (May 2018) https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/ps012

Virginia Tech Extension - "Why Have My Hens Stopped Laying? 5 Factors that Impact Egg Production" (October 2023) https://pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/dam/pubs_ext_vt_edu/APSC/APSC-180NP/APSC-180NP.pdf

Grubbly Farms - "Why Have my Chickens Stopped Laying Eggs?" (September 2023) https://www.grubblyfarms.com/blogs/grubblys-community/why-have-my-chickens-stopped-laying-eggs

University of Wisconsin Extension - "Life Cycle of a Laying Hen" (2024) https://livestock.extension.wisc.edu/articles/life-cycle-of-a-laying-hen/

Hobby Farms - "How Long Do Chickens Live & Produce Eggs" (March 2025)https://www.hobbyfarms.com/how-long-do-chickens-live-produce-eggs/

SPCA BC - "Egg Production in Canada" https://spca.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Egg-Production-in-Canada-Jan-2022.pdf

The Hearty Hen House - "What Things Affect Egg Laying?" (April 2020) https://www.theheartyhenhouse.com/what-things-affect-egg-laying/

American Egg Board - "Industry Data" (2023) https://incredibleegg.org/industry-data/

Colorado State University Extension - "Backyard Chickens" https://sam.extension.colostate.edu/backyard-chickens/

UC Agriculture & Natural Resources - "Basics for Raising Backyard Chickens" https://ucanr.edu/sites/poultry/files/215738.pdf

University of Tennessee Extension - "W1275 Raising Backyard Chickens: 10 Things to Do" https://utia.tennessee.edu/publication/w1275-raising-backyard-chickens-10-things-to-do-that-will-make-you-successful/

Phantom Ecology - "USDA Urges Americans to Raise Chickens as Egg Prices..." (March 2025) https://phantomecology.com/usda-urges-americans-raise-chickens-egg-prices/

Lafeber - "Care of the Backyard Chicken" https://lafeber.com/pet-birds/care-backyard-chicken/

Tilly's Nest - "Flock Safety: Backyard Chicken Predators" (November 2019) https://www.tillysnest.com/p/flock-safety-predators.html

The Chicken Chick - "11+ Tips for Predator-proofing Chickens" (May 2023) https://www.the-chicken-chick.com/predator-proofing-chickens.html

Garden Betty - "9 Ways to Predator-Proof a Chicken Coop" (April 2024) https://www.gardenbetty.com/predator-proof-chicken-coop/

Reddit/BackyardChickens - "Guide: How to Predator-Proof Your Chicken Coop" https://www.reddit.com/r/BackYardChickens/

Humane World - "Adopting backyard chickens as pets" (July 2018) https://humaneworld.org/our-work/farm/chickens/adopting-backyard-chickens-as-pets/

Hobby Farms - "Battery No More: How To Adopt Rescue Hens" (February 2020) https://www.hobbyfarms.com/how-to-adopt-rescue-hens/

Reddit/Vegan - "How do you care for rescued chickens..." (January 2023) https://www.reddit.com/r/vegan/

Open Sanctuary Project - "Creating An Enriching Life For Chickens" (December 2022) https://opensanctuary.org/resource/creating-enriching-life-chickens/

Farm Sanctuary - "Chickens | Farm Animals" (March 2025) https://www.farmsanctuary.org/get-involved/helping-farm-animals/chickens/

USDA - "USDA Update on Progress of Five-Pronged Strategy to Combat Avian Influenza" (March 2025) https://www.usda.gov/news-releases/usda-update-progress-five-pronged-strategy-combat-avian-influenza

USDA - "USDA Invests Up To $1 Billion to Combat Avian Flu and Strengthen Biosecurity" (February 2025) https://www.usda.gov/news-releases/usda-invests-1-billion-combat-avian-flu-and-strengthen-biosecurity

University of Maryland Extension - "Raising Your Home Chicken Flock" https://extension.umd.edu/resource/raising-your-home-chicken-flock

Further Reading & Resources

culling alternativesIn-Ovo Sexing

Step into the egg industry's latest buzz: In-ovo sexing. While sensationalized as “The cutting-edge technology trying to save millions of male chicks from being gassed” and “A Simple New Technique Could Make Your Eggs More Humane” by major media outlets, the truth is more complex.

pARENTINGMotherhood in the Egg Industry

The vast majority of farmed animals, are female, and they are often subjected to unspeakable cruelty in the name of food. This includes cows used for dairy, pigs used for breeding, and of course, the layer hens used for their eggs. But it's not just the layer hens that suffer in the egg industry—it's also their mothers.

Continue reading

GUIDEThe Ultimate Egg-Replacer Guide

Are eggs really necessary? Spoiler alert: they're not! Whether you're transitioning to a plant-based lifestyle or just looking for healthier, cruelty-free alternatives, vegan egg replacements make it easier than ever to whip up your favorite dishes without compromising on taste or texture.